May 4, 2009

San Francisco, California

2commanche7@att.net

By Charles E. Cannon

Formerly of

5726 Bonnell Street

Lake Como, Fort Worth, Texas

Acknowledgments

To my devoted wife Yvonne, and daughter Stephanie, thank you for your wise critiques and the hours of work in editing these short vignettes. You have contributed immensely to a document that expresses the deep emotional ties I have for Lake Como, the oldtimers who lived there, and to a discourse which attempts to convey a colloquial but accurate account of some events from my childhood, as much as memory will allow.

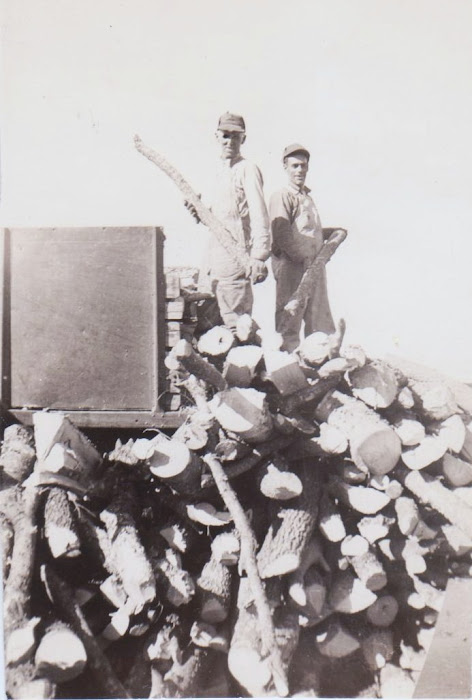

Many thanks to Dena Brown, Reuben Willburn's granddaughter, and her aunt Mrs. Frieda Willburn, wife of the late Reuben Willburn Jr. for contributing the beautiful, priceless family photographs of the Willburns at Benbrook, Texas. My thanks and appreciation also to Patrick, James and Mary Ellen Willburn, and also to Dorothy Willburn (a great Aunt of the above) for their openness to a stranger and their help in making my research a success. Patrick and James Willburn are grandsons of Church Overton Willburn.

Thanks also to James Cass, and Frank Meeks, two other surviving early Como residents. James has visited Como regularly over the years and has kept in touch with the Los Angeles contingent. His memory is superb. Frank never left Lake Como and is still there. C.C.

Visit Warm Prairie Wind's The Sunshine Special

A short account of Como's beginnings, the names of some of the first settlers and a more accurate history by Rubye Jones.

LAKE COMO, TEXAS, NEIGHBOR TO BENBROOK

1930-1945

Preface

The city of Fort Worth, Texas was established June 6, 1849[1]. Near Lake Como and Benbrook, the Clear Fork of the Trinity River makes a long curve along the southern edge of its flood plain and up against steep limestone hills and slopes, swinging north for about 2 miles and joining its confluent West Fork[2], and turning sharply east, then north, before veering south again along the city’s eastern perimeter. The resulting topography became a natural defensive position protecting the site’s western flank and it is one of the likely reasons that what is now downtown Fort Worth sits atop a limestone bluff overlooking and jutting out into the Trinity’s flood plain at the city’s northern end.

The communities to the west of Fort Worth have very interesting origins, both recent and ancient. “Recent” pertains to the mid-1800s occupation and settlement by white people[3], “ancient” relates to the geology of the region. [4] "Prior to the arrival of Anglo settlers, large herds of buffalo and members of the Wichita, Caddo, Comanche and Lipan Apache Indian tribes roamed the Benbrook area. Archeologists estimate that the area has been inhabited for some 11,000 years. Indian communities look for the same environmental factors as present communities, with the availability of an adequate water supply being a primary consideration. Undoubtedly, the confluence of the Clear Fork-Trinity River and Mary's Creek provided such a watering place to tribes as they passed through the area on hunting expeditions." (http://www.cityofbenbrook.com/content/52/85/default.aspx)

In 1930 Como lay on the very western edge of Fort Worth’s city limits which ended at Halloran Street. Beyond the next two blocks west of Halloran was rural countryside. Before the golf course was built the prairie went on, uninterrupted, except for a few scattered farms of wealthy landowners. Not much detail is available telling how Como became a semi-isolated black enclave on the fringes of west Fort Worth. Perhaps we can examine certain relevant events and deduce from them clues which will guide us to a plausible explanation.

Fort Worth Floods 1900-1908, 1922

http://www3.gendisasters.com/texas/9718/fort-worth-tx-flood-sept-1900

(THE TRINITY RIVER HAS FLOODED FORT WORTH

“…It has been many years since the waters of the Trinity have reached such a high stage. As yet no loss of life has been reported but it is reported that possibly some people have perished below this city in the Trinity river bottoms by the unprecidented (sic) overflow…”).

The excerpt above is from an early regional newspaper and it provides some clues of high potential. The Trinity River has flooded periodically for thousands of years, long before humans were here. Usually it is a placid stream, its Clear Fork flowing from the west-southwest and its West Fork flowing from the west and northwest with a high plateau watershed over a hundred square miles in size separating the two forks before they converge at downtown Fort Worth. Rainfall can sometimes be excessive, causing the river to overflow its banks and spread out over its wide flood plain, submerging everything in deep, swift-flowing waters.

The flood-prone steep slopes below the courthouse and the low-lying benchlands on the city’s eastern edge were not places where whites would choose to settle despite their closeness to town. Mrs. Corrine Clemons, who once lived below the courthouse, used to tell stories about some of these floods, how the police would knock on doors in the middle of the night telling people, "Get out, the river is rising." But it is these locations that were left which poor ex-slaves were able to claim. It took years and successive floods before the blacks living here found a racially unrestricted area on high ground that was also affordable and where a community could expand. Lake Como turned out to be that place.

Perhaps it was a combination of two unrelated calamities that made black settlement here possible; the disastrous early Fort Worth floods and the financial failure of H.B. Chamberlain’s speculative amusement park venture in West Arlington Heights.

OLD LAKE COMO

The African-American community of Lake Como not long ago celebrated its own one-hundredth birthday[5] (July 2006). The actual date of birth is an indefinite moment when the first person of African ancestry erected the wooden foundation posts for his home or moved into a structure formerly occupied by whites. This story spans only fifteen years of history, roughly from 1930 to World War II’s end in 1945. It is only a short snippet of history, albeit a crucial period in U.S. and world history, for it covers the time beginning with the disastrous financial crash of 1929, includes the rigors and trials of the Great Depression, financial recovery and victorious war in 1945. The chaos generated by both events had a great effect on Lake Como’s population as it did universally. The history of the years before and after these covered here will have to be addressed by future research and reporting.

To stand upon the ground in Lake Como is to stand upon an ancient seabed.[6] The fossilized remains are everywhere and in some places a limestone composite more than fifty feet thick. Stoop down anyplace and pick up a piece of stone, examine it, notice the swirls and ridges etched into its surface. Or go out along the old Stove Foundry Road[7] to where the driveway led up the rise to Doc Brants’ house.[8] If there is still access, stand on top of one of the vertical cuts of the roadside. Again examine the rocks at your feet; they are evidence of the region’s earliest living inhabitants, ammonites and little snails that grew here sixty-five million years ago. If it is spring, look among the stems and green leaves of the wildflowers growing out of this mix of prairie topsoil and limestone; see the live snails crawling there now, compare them with the snail fossils that look like small pebbles. These fossils’ live descendants look like they have not changed in sixty-five million years. The experience makes one feel very insignificant.

This was Comanche country and that of other tribes as well. The Chisholm Trail went through here. Lake Como, Benbrook and the whole Trinity-Brazos River watershed had to have also been Comanche territory prior to white settlement. The White Settlement Road going to the northwest out of downtown Fort Worth no doubt marks the incursion by Europeans into Indian territory. Beautiful rolling prairie, as late as the mid-nineteen-forties under cultivation or grazing land remained in many ways much as it was when the Comanche lived and hunted here.

With the spring rains came a profusion of wildflowers―Bluebonnets (Lupine), Winecups, Indian Paintbrush, Evening Primrose, Daisies, Gaillardia (Indian Blanket) and other Texas prairie wildflowers[9]― which after bloom were deprecated as weeds. Easter season was truly glorious. The earth was a natural painted canvas leg deep in the most gorgeous colors. Heavenly spring and early summer days, the sky bluer, the air sweeter and fresher, and the sunshine more comforting here than in any other place on earth. Even the storms were more spectacular in the terrible beauty of their fury.

To Remember a Fort Worth Storm

Spring and summer storms in Texas can be very violent and for those who can appreciate them also quite beautiful. Sometimes on a lovely sunny afternoon Charles’ mother or his aunt Ellen would announce, “There’s a storm coming.” Looking out from the kitchen window over the sink; a little way above the horizon in the north was a very black cloud that seemed to be advancing from the west. It moved fairly fast and its head seemed to turn south toward Charles’ house as it also filled the sky towards the eastern horizon. It was black, black, black, but the sky ahead of it and towards south Fort Worth was bathed in radiant sunlight.

As it drew closer, the clouds forming its head towered up, up, and boiled. Charles watched, fascinated and scared. He watched as its front became even with the electric power lines in the alley behind his house and as the sunlight yielded its radiance to the blackness. Suddenly the storm would strike with all of its violence. The lightning flashed and made zig-zagging streaks across the sky, sometimes flicking and trickling, lighting up the entire sky, and the thunder sounded like there were angels overhead hurling huge boulders across the heavens that collided with other cosmic stones in the distance. It sounded like explosions were right on top of the house. They echoed, and reverberated, and cascaded away into infinity and then were temporarily pacified in moments of silence, except for the roar of rain and hail which pounded the roof. The deluge plunged off the house’s eaves and down Bonnell Street’s gutters headed for Como’s swollen streams in torrents that struck obstacles and surged up more than two feet high. Often these storms were more than Charles could handle, so when the thunder sounded like it had actually hit the roof and the lightning flashes came in such quick succession that they lit up the bedroom brighter than the sun, he would duck under the bed and close his eyes and not come out unless forced out by an adult or the storm had moved on. Sometimes, when there was enough daylight left, the sky would clear and the sun would come out and shine as if there never had been a storm. Later, stars would appear in the night sky, making a million little twinkling lights and the Milky Way scattered itself across the firmament like a trail of white smoke from a prairie wildfire in heaven.

To remember Lake Como is to remember the sounds of a million frogs croaking before midnight in the streams and ponds, the melodious warbling of a mockingbird in the light of a full moon, the first distant rooster crowing at three A.M. and minutes later a nearby response, until the dawn was filled with a raucous chorus celebrating a new day; Ben Littlefield’s mules braying at sunup, the whistle of the Sunshine Special heading for El Paso in the afternoon and Momma Cannon in the backyard singing “Amazing Grace.” These sounds made Lake Como and the surrounding countryside, in early times, a truly unique and special place to live.

Except for a few small patches here and there, these expansive miles of wild beauty where buffalo once grazed, have morphed into housing developments and commercial shops.

The earliest black old-timers, who have remained here into their seventies and eighties or older, are witnesses to an epochal change like that encompassing most of the world; preparations are now underway to drill for oil and gas[10] just across from Como Cemetery. Whether they realize it or not, their personal experience of social oppression, poverty and their struggles to overcome them, their faith in God and the natural beauty of this place combined into one essence to make them who they were and are.

Lake Como Cemetery

(An Internet photograph of a wrought iron gate[11].)

Lake Como Cemetery Elegy

Most of those buried beneath that hard earth

lie in unmarked graves.

Galvanized markers long ago disintegrated.

The names and images of the dead missing

from the conversations of visitors

privileged to walk here now.

The deads' loving kin also lie at rest close by.

Or in other cemeteries far across Fort Worth,

beyond intimate mourning.

All eventually will be forgotten.

But while we who are alive still remember,

let us sing songs of mourning love.

Sing them in the verdant spring.

Sing them in summer’s scorching heat.

And cast plaintive melodies into winter’s cold winds,

November northers that blow across this bare prairie slope

when its tall grasses too have died

and brilliant summer skies turn slate grey.

Sing too, you the dead, sing your lonely notes.

Be present when we also come in death

and welcome us with laughter.

Most Unforgettable Characters

Some were pillars of the Como community, deeply religious men and women of the highest character and integrity; loving, hardworking family men who were the salt of the earth, upstanding women who worked to help support their families, who taught their children by example how to be honest, kind, helpful. These were some of the earliest settlers in Lake Como. Some were simply lovable individuals and gracious neighbors. Most of them, regardless of character or reputation, were witty, full of quick humor that separated them from the average person.

Some men were gamblers, bootleggers and self-described hustlers out to make a few opportunist dollars. A very few would be reduced to taking a life. Their common denominator was poverty and a lack of proper education. However, lack of education did not mean ignorance. Their unforgiving vocations demanded smartness, a quickness, an aggressiveness, and an intelligence comparable to that possessed by captains of industry and politics. They were “the good, the bad, the ugly,” and the beautiful.

Those men and women whose names the author has listed, out of hundreds, were chosen because of some particular memory which has significance to the writer, some told here. And because, like most early residents of Lake Como, with one or two exceptions, they have gone to their reward. So don’t look for them on the sunny side of the sod. And they are unlikely to sue the author for making uncomplimentary remarks.

Lake Como Men―

Uncle Jack Mabry

Lewis Meeks Sr.

Reverend G.W. Burton (Zion Baptist Church)

“Uncle Took”( Mr. Boyd)

Reverend Richard Weaver (AME Methodist Church

Collie Sweeney

Joe Sweeney

William Howard Wilburn, Sr. (Editor and publisher of Lake Como's Newspaper)

Will Owens

Sterling Mays

John Adkins (school custodian)

Orenthus “Baby” Meeks

Ben Littlefield

Eugene "Red" Baker

"Six" Williams

“Stack of Diamonds” Freyerson

Jeff Nelson

“Snokum” Russell

Lawrence “Brokie” Cook

John Douglas

Pop Valentine

Elijah White

Ned Slater

Robert “Kootchie” Marks (consummate caddy and golfer)

“Mummy” Marks

Garland Ross

“Pee Wee” Williams

Douglas McWilliams

“Sonny Gunny”

Lake Como Women―

Willie Cannon (“Momma Cannon,” cook for Paul Waggoner, heir of wealthy oilman W.T. Waggoner, and Helen Waggoner, whose residence was in the Texas Hotel in downtown Fort Worth)

Josie Bennett (laundry-woman, she and husband Gus raised cows and chickens)

Viola Richardson (mother of Leon Griffin)

Amelia Littlefield (strong high cheekbones, light-skinned with long dark graying hair below her waist, of black and Indian ancestry)

Sarah Mabry (cook)

Hannah Mae Mays

Eula Johnson

Mrs. Patterson (longtime Como school teacher, teacher at both schools)

Mrs. Stearns/Smith (early principal and teacher when school was on Bonnell and Faron, later married Charlie Smith when Stearns died)

Rubye (Crawford) Jones (teacher at both schools)

Miss Lois Carr (teacher at both schools)

Miss Theis (teacher at both schools)

Mary D. Lewis

Lillie Belle Patterson

Addie Latimer (white school custodian)

About Some Unforgettable Characters

Lake Como had some very colorful characters. The names of many of them appear above. Ben Littlefield, Six Williams and Red Baker were known by everyone and despite their part-time illegal bootlegging operations they were loved and well respected.

Ben was married to Amelia (Littlefield) who had a cow named Blossom, a prolific processor of Como’s prairie grasses and a producer of fine dairy foods. Blossom was a very finicky cow. Stick a finger in her drinking water and she’d refuse to touch it until the trough had been drained and refilled with fresh water.

Ben Littlefield

When Ben was not making “white lightning” with Six Williams, he worked six days a week hauling landscaping soil and whatever other work he could find for his teams of mules and assortment of mule-drawn ploughs, Fresnoes (the forerunner of the mechanical bulldozer used to move loose earth), and wagon. At day’s end he would unhitch the teams, feed and water them, bathe and dress, eat Amelia’s excellent dinner, then stick his 45 Colt revolver under his belt and mount one of the mules to go for a night of gambling. Ben was also a heavy drinker, especially in his later years after Amelia left him. He used to drink with Charlie Smith and Uncle Andy down at Smith’s Barber Shop at the corner of Faron and Bonnell Streets across from where Como‘s grade school used to be. Ben went there in a small wagon drawn by a little long-eared burro. Ben would go inside and drink himself into a stupor while the burro waited, and wait he did, sometimes all day and all night until someone would finally hoist Ben up into the wagon and say “Get up” to the burro who slowly plodded home without human guidance, down to the Stove Foundry Road across from where the golf course ends. Ben’s “live-in” woman would unhitch the critter and put Ben to bed. More than once the animal tired of waiting and went home of its own accord, leaving Ben behind.

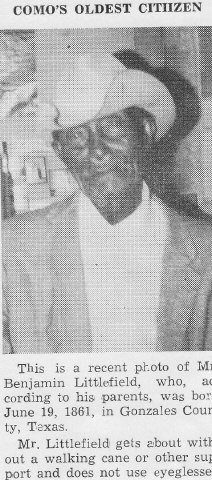

Both Ben Littlefield and Six Williams raised greyhounds and a few bloodhounds and they hunted together down in the Trinity’s river bottom at night for raccoons, opossums and other little creatures that no one ever saw unless they were zoologists or they were Ben Littlefield or Six Williams. Some days were spent hunting jackrabbits on the prairie surrounding Fort Worth, sometimes many miles from Lake Como. Men, boys and dogs would be loaded onto the back beds of a couple of trucks and they would set off for a day of high adventure and entertainment. The animals caught would be eaten by friends and neighbors. A mixture of black and Indian ancestry, Ben is said to have lived to be a hundred years old.

Red Baker

Eugene "Red" Baker and his wife were very likely early residents. He was about six feet tall, grizzled and slightly stooped, very light skinned with a reddish hue that betrayed his mixed ancestry. He had a thick mustache, protruding reddish lips and sandy brown hair. He had a loud voice and employed it effectively to communicate his frequent anecdotes.

Red Baker lived diagonally across from Ben Littlefield on the corner of Horne and Bonnell.

His wife was dark brown and a wisp of a woman. Red and his wife to all appearances maintained a peaceful marriage, but one day something happened to break this peace. Early in the morning they began to argue, the argument got louder and angrier, soon they were physically fighting. Both were bloody by day’s end, but by sunset things were silent and people thought that all was resolved. However, not long after sunup they were at it again. Everyone expected someone to be killed but did not intervene. Again they fought all day long, stopping to rest sometimes for an hour or two before resuming the bloody fracas. The third day was a repetition of the two preceding it, but to everyone’s amazement both were still alive when it ended. No one ever knew the reason for this terrible battle. Sometime later, Red and his wife moved away from Lake Como to parts unknown and this episode in the saga of Lake Como was forgotten until now.

Six Williams

Periodically the Texas Rangers came to town and raided the stills of bootleggers, but somehow Ben, Six and Red always eluded arrest. They had friends among the local police and were usually warned ahead of time. Once the Rangers went to Six‘s place up across from where the Blue Bird Café is now to see what they could net. They went into Six’s backyard, and spotting a large tub of fermenting grain, asked Six what it was. He calmly pointed to his pen full of hogs and replied, “Hog mash.” Outwitted, the famed Texas Rangers left the scene empty-handed.

Crissy Nelson

Matriarch Crissy Nelson lived next door to the Cannon family on Bonnell Street with her three daughters and son Jeff. Over time Mrs. Nelson lost her husband, a son, a daughter and a grandson to the violence endemic to black communities, although their murders did not occur in Lake Como.

Mrs. Nelson, “Grandma Nelson,” became a mentor to young Charles Cannon because his own parents were absent most weekdays due to their employment. He regarded her home almost like his own. Mrs. Nelson counseled him as she once had counseled her own son Jeff, who had long since abandoned his mother’s guidance. A habitual dipper of Garret’s Snuff, a most foul powdered form of tobacco, she did her very best to dissuade Charles from smoking cigarettes at age twelve and was a good companion to him despite her seventy-some years of age.

Mrs. Nelson had been widowed years earlier and was supported by her children. In these years there was no social security or pensions. W. Lee O’Daniel[12], Fort Worth Burrus flour mill executive and newly elected Texas Governor, had included in his campaign, promises to do more to help aged and needy people. Charles used to hear Mrs. Nelson lament about her plight, so one day he suggested to her that she write the new governor a letter asking him for aid in obtaining some sort of pension. They drafted a letter, mainly using the words suggested by Charles, and mailed it to the Governor in Austin, Texas. Sometime later Mrs. Nelson had a visit from a social worker that resulted in her being awarded a small pension.

During his extremely popular campaign, O’Daniel visited many localities in person, bringing with him his “Light Crust Doughboys,” a cowboy band, and a motorized wagon fully equipped to prepare freshly baked hot biscuits which were buttered and handed out to the approving crowds. He visited Lake Como on more than one occasion. One memorable event was held in front of Holloway’s Grocery at Littlepage and Goodman streets. Somehow his persona was tagged with the by-name “pass-the-biscuits-pappy." Everyone knew who he was, his election was almost assured.

Jeff Nelson

Jeff and Charles, whom Jeff nicknamed “Smokey,” became close buddies after Charles’ dad’s death in 1940, despite the fact that Jeff already had grown children who lived independently. Jeff was what was known as a “hustler,” a person who had no job and did not seek employment of any kind. He never cursed and never went to church until his last years. When he had not disappeared on one of his gambling junkets somewhere in West Texas, he mainly gambled in the gambling den (the former West End Café) up on the corner of Wellesley and Horne Streets, if he had money for a stake. When he did not have a stake he would devise the tools to acquire funds by obtaining three soda pop tops and bending them so that a little ball or a pea could be slipped under the bend in the middle and easily shifted from under one top to another, for a game that he called “The Greasy Pig.”

Jeff would wait for the high school shuttle bus bringing students home from I.M. Terrell (a school bus finally provided in 1938 for black students) and cajole some of the kids to bet on which cap the “pig” was under. It was almost a one-hundred-percent losing proposition for the kids and Jeff would get enough money to enter the bigger dice game a few blocks away. Although Charles often followed Jeff to the big dice house, he never remained there long or gambled because he knew that this was a dangerous pursuit and an unsafe place to be.

Charles and Jeff made Choc together, a homemade alcoholic brew consisting of fermented dried fruits and copious amounts of sugar, malt and water. Three or four Texas summer days in a five-gallon clay-fired “Croc” pot matured the concoction into a pretty powerful amber-colored beer-like liquid, and if a large piece of ice was added to the container, a very enjoyable and refreshing drink relieved the summer heat. The two spent many afternoons together drinking and talking and Charles and Jeff remained good friends in the years after Charles left his Lake Como home in 1944 to live in California.

Doc Brants, Ernest Allen and the Willburn Brothers at Benbrook

Doc Brants’ river-bottom fields and woods were wonderful places for hunting ducks, squirrels and an occasional ’possum. Every year, when school let out at noon for Thanksgiving holiday, a group of kids would hike down along the Stove Foundry Road just exploring the countryside. Eventually they would end up seeking the pecan trees scattered among the more numerous oaks. A few of the trees produced large soft-shelled nuts to be gathered up and eaten by a nice warm fire.

Doc Brants’ home place was on the north side of the Stove Foundry Road not far from where it intersected the Benbrook Road; it extended all the way over to Camp Bowie Boulevard and the highway triangle where the Trading Post was (the local watering hole for the region’s drinking white men). Doc grew wheat and when harvest time came, he hired day laborers, some from Como, to shock and thresh his wheat. One of Charles’ first farm jobs was for Doc’s wheat harvest.

Charles also worked part of a summer at Ernest Allen’s, the Fort Worth Chevrolet dealer who also had a farm roughly opposite Doc’s place. He raised beef yearlings and pigs. These animals were subject to injuries from fights, especially the pigs, and had to be inspected every other day for flesh-eating worms spawned by flies. Too much time elapsed between discovery and treatment could and did sometimes prove fatal to the animal and even in lesser cases, despite treatment and eradication of the carnivorous worms, the resulting injuries could still be serious. Each animal had to be individually inspected for the slightest cut and have “fly dope” applied to the wound to prevent flies from laying eggs in it. If fly larvae were already present in the wound, eating the pig’s flesh, the wound had to be chloroformed and the larvae removed.

About the time Fort Worth was founded in the 1840s, nearby Benbrook was also being established by white pioneering families. On the river-bottom flood plain along Mary’s Creek and over towards the small farming and ranching community of Benbrook, lived two white brothers, the Willburns, who were direct descendents of the region’s first white settlers.[13] Reuben Willburn and his brother Church lived on side-by-side farms across the railroad tracks on Stove Foundry Road just before it intersects the Benbrook Highway west of the Allen place.

Reuben Willburn was a woodcutter and supplier of heating firewood for Lake Como’s stoves. During the summer months he also was a contract hay baler servicing nearby landowners, some of whom owned extensive acreage passed down from pioneer scions. At times he employed day laborers from Como. He was a customary presence in the community and he had very friendly relations with its people, especially Uncle Jack Mabry, and those he hired. The author knew and worked for both as a youth in the late '30s and early '40s. The experiences of knowing and working for the Willburns helped to prepare the author for the rigors and trials of later life. They are indelibly etched into his memory in love and respect. God bless them.

Reuben ran a hay baling business during the summer months. Charles’ first summers helping harvest were done the old-fashioned way. The hay was cut and allowed to dry, then windrowed with a horse-drawn sulky rake. When time came to bale it, a wide flat buck rake drawn by two horses, Sorrel Top and Popeye, harnessed ten feet apart on either side of the eight-foot-deep wooden-toothed rake, would be guided down the long thin rows of hay until the hay was piled up as high as the horses. The rake was then driven to a stationary hay press powered by a long leather belt placed around the power take-off wheel of the John Deere tractor, and Willburn or his helper, Pancho, would pitchfork the hay into the hay press. Popeye worked on the right side of the buck rake and had to be forced to go near the noisy machine. He was reluctant for good reason; he had some years before lost his right eye in an accident that happened at the hay press.

Sorrel Top was an aggressive horse. He was strong and at times could be very difficult to manage. If he did not feel like going to work in the morning he could be impossible to catch and harness up. Once, his owner, Church Willburn, had to be summoned to catch him. He was forced into his corral by Church, the entrance gate was closed and Church proceeded to beat the animal about its head with the bridle. For a time it was difficult to determine who was going to kill whom. Sorrel Top reared up on his hind legs and lashed out with both front iron-shoed hoofs as Church struck him with heavy blows. After a while Church opened the corral's gate and stepped outside and held the bridle open about shoulder high and told Sorrel Top to “come and get it.” The horse slowly walked forward and put his head into the bridle. He was a very good horse for days after.

This animal could also be mischievous and calculating. During a period when Charles was hauling hay from the large sloping field on the other side of Mary’s Creek, Sorrel Top displayed more of his ingenuity. The road from the field to the barn passed through a fence gate before it turned sharply right, then paralleled the creek where the water was deep before reaching a shallow rock-strewn crossing. Charles would stop the team, get off the wagon, piled high and heavy with baled hay, remove the wire loop securing the barbed-wire gate, pull the gate out of the way, then tell the team, “Get up,” and wait for the wagon to pass through before saying, “Whoa,” halting the wagon and re-closing the gate. Charles would then climb back over the wagon’s rear to his driver’s position. This went without incident for a few times until Sorrel Top figured out how to get his way. As soon as Charles left the wagon and was in no position to see the horses, Sorrel Top would swing his tail high above his rump, getting the reins under his tail and clenching it there so that the driver had no control and he would take off running, sometimes dragging the other unsuspecting horse down on its knees and pulling it and the heavily loaded wagon down the road and into chest-high water where he stopped to cool off. Well, after a few episodes of this, Charles, too, gave him Church’s bridle treatment with the ends of the reins. Sorrel Top became a bit more manageable after that.

Church Willburn was fifty-two or fifty-three years old, a good man not given to foolishness; he had a deep voice, a pleasant but firm demeanor and he behaved and spoke with a confidence that commanded respect. In the field, all the hands drank from the same water can using the same cup. Both Willburn brothers loved their booze and did not shrink from sharing the same bottle, drinking from it with their workers. Once when they were baling hay for Mr. Corn, a Benbrook landowner, the old red-faced man came out into the field and handed them three pints of IW Harper, saying, “Maybe this’ll help you boy’s baaale a little more hay!”

Reuben sometimes would stop at the Trading Post and have Charles go in and purchase a bottle of cheap red wine which Charles didn’t like and didn’t drink. Charles drove the John Deere tractor that pulled the pickup hay baler up and down the windrows. Reuben Wilburn watched the hay go into the receiving bay, its compacting by a mechanical arm, then pressed backward into the press. Then the bales were blocked and tied by two Mexican workers, Pancho and Pete. The tractor’s exhaust pipe was right in front of the driver and its poisonous fumes often blew back in Charles’s face, some days making him dizzy, almost unconscious. Pancho and Pete used to keep large clods of dirt handy to throw, hitting Charles on his back to keep him awake, preventing him from going to sleep and falling off the tractor and being run over by a driverless machine.

Pete, like Pancho, had an ageless look. Short and spare like Pancho, he was also friendly and full of humor―he and Pancho joked a lot. His family still lived in Mexico and he sent money home. Pancho had an engaging smile that exposed his discolored teeth and he wore a sweat-stained felt hat over his full head of black hair. Pete wore a Mexican-style straw hat. The men lived together in a small one-room pine board shack with a dirt floor and a tin roof, a few hundred feet behind the Willburn’s family home and not too far from the creek. One late afternoon as they were baling Mr. Corn’s hay, Pete spied a good-sized armadillo catching insects in the alfalfa that had been disturbed by the baler. He grabbed a ball-peen hammer from the metal top in front of him and gave chase after the animal, quickly catching it and killing it with a single blow to its narrow head. Mr. Corn’s hayfield was very near where the men lived and they always went home for lunch. This day, after the little critter’s demise, the men invited Charles to come home with them to lunch on armadillo. It had been prepared in a thick chili and it was the most delicious meat that Charles had ever eaten.

Early one morning, as Charles climbed into Reuben Willburn’s truck, he was astonished to see a 32/20 revolver lying on the seat between them. He asked Reuben, “What’s that for?”

Reuben replied, “That’s for Pancho, we had a fight and he hit me. He’s gone but if he comes back I’m going to kill him.”

Charles was very saddened to lose Pancho and also to see Reuben in such an angry state. The man had always been friendly and peaceful, ungrudging and helpful. It was the saddest day he’d ever experience while working for the Willburns.

In the summer, Reuben Willburn used to cut oak and other wood for firewood which he sold in Lake Como from a wood yard near Bonnell and Horne. This is where Charles first became acquainted with him. At that time all of Como’s residents used either wood or kerosene to heat their homes in the winter and for cooking year round. There was no gas pipeline servicing Lake Como and for many no electricity either. It was through this enterprise that Reuben Willburn acquired black friends and acquaintances.

It was also during this time that Charles learned of Reuben’s recurring accidents involving his tractor, which Charles would drive a few years later. The John Deere tractor had a power take-off wheel on its left side right by the engine which was in front of the axle and the big wheels carrying the tractor. It was in this vulnerable spot where one stood to crank the engine. Before attempting to start the tractor‘s engine one first examined the gear lever where the driver sat to ensure that the gear was in neutral and not engaged or partially engaged. If either condition was true, then when the power take-off wheel was grasped and turned, starting the engine, the tractor would lurch forward, hitting or running over the person trying to start it. Reuben’s proclivity towards intoxicating beverages and his proximity to farm machinery put him at high risk for serious injury and the inevitable happened more than once. Fortunately, he always survived and only suffered severe bruises and lacerations. He was a very skinny, wiry, thin-haired blonde man of average height. Ordinarily very fair, his exterior had been weathered, beaten, tanned, and toughened by years of exposure and hard work. He was a good man who fathered several children and for whom Charles developed a real love.

The first time Charles ever drove any vehicle except a tractor was when he and Church Willburn were hauling hay and Church needed a truck. Church had purchased a bottle of whiskey that morning and both he and Charles (about fourteen at the time) were feeling no pain. So Church told Charles that they had to go down past the Texas and Pacific shops towards town and rent a truck. Charles realized that there were only the two of them and Church would have to drive his car. Charles asked, “Who’s gonna drive the truck?”

Church drawled, “Why you are!”

They went down and rented the truck. With Charles driving the truck, drunk as a skunk and scared to death, he followed Church the four miles back up Stove Foundry Road to Church’s place. Not many people traveled that road back then and they met no other vehicles on the way back.

It was during this harvest time that Charles first sat at the same table and ate a meal with white people. It was late in the evening and almost dark when Charles finished the day’s work. He lived two-and-a-half miles away over in Lake Como. Mrs. (Cana) Willburn came out and said, “You are having dinner with us tonight and Church will drive you home.” Charles did not know how to react, white people did not eat with blacks and this was very unusual. Both Church and Mrs. Willburn were very gracious and pleasant during the meal and that night made a lasting impression upon Charles. He used to think that all white people were hateful and there were times when he hated them right back, but that night he learned something new, that all whites were not hateful.

Mrs. Willburn loved animals, even the wild ones down in the river bottom. Church once told Charles, “Don’t ever let her know that you hunt down there.” Charles came to know that animal lovers were usually lovers of people too.

Charles saw Reuben last in 1949 on a visit home from San Francisco. He was sitting on Uncle Jack Mabry’s front steps visiting and talking. They were very happy to see each other. Reuben Willburn and his brother Church Willburn remained in the area at until shortly before the 1950s, the family farms were sold and the land is now a housing tract. Freeway 20 encircling Fort Worth has replaced the hayfield above the creek.

Mr. Lewis Meeks, Sr.

Charles’ father, a Pullman porter, died when Charles was twelve. His death left a great empty space in Charles’ life even though his dad was away for most of his childhood. Mr. Meeks lived behind Zion Baptist Church at Libbey and Horne with his wife ’Celia, sons Lewis, Jr. (“Son”), Orenthus (“Baby”), Bob, and daughter “Sis.”

The Meeks boys were caddies at Ridglea. Baby, being the oldest and most assertive, was the leader of a small group of boys that included Walter Weaver, Charles’ best friend. Baby owned greyhounds and a 22 rifle. He enjoyed hunting. Charles’ close friendship with Mr. Meeks, Sr. began as a result of his friendship with Baby.

Lots of people had a need for someone with a truck to haul various things and do jobs requiring manual labor. Mr. Meeks and his sons were very good workers and always in demand. Charles was often included in the work projects. By the time Baby went into the Marine Corps, so many young men had left Lake Como that Charles was left adrift with no real friends near his own age with whom he had common interests. Charles quit school at fourteen, capitulating to his inclination to work, not only because it was necessary but because it was also very satisfying. Son, Lewis Meeks, Jr., was killed in a vehicle collision, driving between Fort Worth and Dallas, not long after he married Florient Bowles. This void in the Meeks’ family and work team nurtured the relationship between Charles and Mr. Meeks. Meeks became a father figure for Charles at a time when he desperately needed one. The man and the boy worked harmoniously together hauling lumber, cement and performing various construction tasks. The two thoroughly enjoyed each other. Charles began to learn the ways of manhood and acquired a work ethic that would last a lifetime.

The elder Meeks and Baby were both dedicated members of Zion Baptist Church and were available for Reverend Burton’s needs at various times, always performing caretaker tasks. Baby and his dad were very close and Charles was happy to be on the periphery of this relationship.

Roscoe Perkins

Roscoe was a delightful friend. He was very light-skinned with tight, curly, brownish-black hair. He was portly and smoked cigars. He usually had two or three tucked into his shirt pocket. Roscoe loved to shoot dice and eagerly got into any crap game he encountered. He also carried a long-barreled 32/20 holstered on his belt when he went out around Lake Como. He was married with one child and his wife was expecting their second. Like all of Charles’ few close friends, Roscoe was much older than he.

The year was 1943 and both worked at the American Manufacturing Company hauling the oily steel turnings from the lathes, which were operated only by whites, to the gondola scrap cars, dumping them there. This company had made oil field machinery before the war but had been converted to manufacture 75 and 155-millimeter artillery shells for the army. Charles and Roscoe worked the graveyard shift. They had to travel by bus to a location diagonally opposite Lake Como on the Northside which sometimes took almost an hour. The bus ride gave them time to be together and talk.

Roscoe also loved to hunt and this common interest is what cemented their friendship. Often they would come home in the morning and go out on the prairie or down in the river bottom hunting rabbits, squirrels, quail, doves, and on a rare occasion, ducks. One day, while down in Doc Brants’ wooded portion of his riverside field, they heard the loud quacks of ducks. Knowing where the ducks were, at the waist-deep cattle tank, they got down on hands and knees and crawled there, unnoticed by the ducks almost to the very edge of the pond. Their plan was to get off one barrel from their double barreled shotguns while the birds were on the water and a second shot as they lifted off to flee. The plan worked perfectly and both hunters felled three or four ducks each. The remaining ducks flew away, but the hunters reasoned that maybe if they were patient and waited long enough, the ducks would return. So they stayed, concealed themselves and waited. It took almost two hours and sure enough, two ducks flew over, circled and then landed on the pond. Roscoe and Charles remained in hiding, not moving and observing the ducks as they swam around. After about half an hour the birds rose and flew off in the direction of the river. Within an hour the whole flock returned, landed and the deception was again rewarded with delicious Teal duck for dinner. This unlikely friendship ended when Charles left for California and became a welder building cargo ships in the war effort.

Several years later, Charles was at his cancer-sickened mother’s bedside as she died. It was a somber, heart-wrenching experience that cured him forever of wanting to kill anything again.

A Narrow Restricted Society

In those years it was difficult for younger people to comprehend how recent slavery had been. Some of the older people had been born immediately after the Civil War and Emancipation. A few Lake Comoans had actually been born slaves. Mother Harper told Zion Baptist Church’s congregation stories of her slave experiences at the annual Nineteenth of June Emancipation Day celebrations, a very happy day with barbequed pork ribs, beef brisket, and all of the trimmings and desserts provided by community women. The congregation was awestruck by her stories and those of others who had been born slaves.

The plight of black Americans in most American communities is a racial conundrum. The origins of social problems are well known and extensively documented, but it is in the functional dynamics of even today’s society that solutions to the legacy of slavery remain elusive and unresolved. Lake Como could easily provide a litmus test for an investigation into the problems arising from race in the United States. Although the corrections won by the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s resulted in the exercise of freedoms and opportunities never before obtained by American blacks, much remains to be accomplished. For a large number of black youths today, the most profound improvements can only be realised through cultural changes, intellectual advancement, and from motivations within the black psyche itself. What the catalyst for this will be, is the most elusive mystery of the puzzle.

Before and during the years covered by these vignettes, opportunities for blacks were, with rare exception, nonexistent, no matter how intelligent or well-educated an individual happened to be. There just was no way, zilch, for the black worker to advance beyond the confines set by state and local laws and the white customs which prevailed following the Reconstruction period after the Civil War. The best jobs and social opportunities were reserved for white people and black citizens subsisted at or only slightly above the poverty line, deprived of both social and economic benefits. It is within these confines, where race determined everything, that these stories evolved and must be viewed.

“In The Valley Of The Shadow Of Death”

To omit a discourse upon the ever-present darkness lying just below the surface of Como’s collective consciousness would constitute a denial of the obvious. As in so many black communities, murderous violence is too often loosed from its weak restraints. Killings arising from uncontrolled anger, simple malice, hot passion, revenge and plain craziness, sometimes fueled by alcohol and, in more recent years, drugs, cut short many lives. Sudden fatal encounters are a constant threat to young black males and females, whether innocent or involved. No one knows when he or she might become a victim. The forces of social malfunction are in play to such a degree that no interventions to end this fratricide have proved successful.

Everyone in the black community can recite a litany of terrible murder stories; they are unforgettably stamped in memory. In 1940, on Easter Sunday, the day had begun like so many Lake Como Easter Sundays before, warm, splendidly sunny, beautiful, peaceful, the prairie wildflowers in their full glory. That afternoon, three Como youths were proceeding down Bonnell Street when an automobile occupied by adults from the Northside drew near. For some totally irrelevant reason, inflammatory words were exchanged and threats were made. The occupants in the car were alleged to have displayed guns. There had always been a certain amount of rivalry between Lake Comoans and Northsiders, but it had never produced the kind of horrible violence that occurred that Sunday afternoon.

Two of the Como boys were brothers, and they went home and told their father what had happened. He and his sons armed themselves and went after their antagonists, finding them in the vicinity of Crook’s cow pasture somewhere between Blackmore Street and the Stove Foundry Road. A running gunfight ensued; when it was over the Como father and one son had been seriously wounded, the other son was killed, and all of the Northsiders had also been seriously wounded and one killed. The father of the third Como boy wisely prevented him from joining his friends, possibly saving his life. The surviving family was reported to have moved to Oklahoma.

The Texas And Pacific Railway (the TP)―Round House And Engine Repair Shops

The railway engine repair shops and switching yards[14] were located near and adjacent to the southeast corner of Lake Como community on the south side of the Stove Foundry Road. Some of the men of Lake Como were employed by the TP through the 1950s and possibly later and saw the demise of those magnificent steam locomotives after WWII’s end and their replacement with the introduction of the diesel locomotive. Men like Como residents Gus Bennett and Grigsby Baker (both deceased) performed the heavy manual labor maintaining the railroad’s equipment. Mr. Bennett came from Marshall, Texas early on, first living on the Southside, moving to Como in the mid-1930s. Grigsby Baker had Baby Meeks as an apprentice in the shops upon his discharge from the U.S. Marine Corps at the war’s end. Baby retired from the TP many years later.

Dozens Of WWI Steam Engines

When WWI ended there was no use for the hordes of steam engines built to haul the nation’s war supplies. Dozens of these huge engines sat lined up in rows end to end in the TP’s repair facility[15] until the very late 1930s when they began to mysteriously disappear. Obviously someone knew we were going to war soon and those engines would be needed again. By about 1941-42 they were all gone, refurbished and pressed back into service hauling troop trains and the machinery of war.

A Re-Icing Stop For Cold-Storage Trains

Also along this stretch beside the old Stove Foundry Road (now West Vickery Blvd.), immediately west of the shops was the TP’s icing facility for the eastbound Pacific Fruit Express.[16] Trains stopped here to replenish the ice in the insulated boxes on the ends of the produce-carrying boxcars. Young men from Lake Como helped restock these cars with ice to complete the eastward journey.

Railroad Switching Yard

The switching yard with its humping operations[17] was here too; and especially during the war years the yard was busy 24 hours a day breaking up arriving freight trains, switching cars bound for different locations onto a host of other parallel tracks and making up altogether new trains. The wee hours of the morning resounded with the chooo, chooo, chooos of the switch engine in quick succession, then silence and next a bang! bang! as cars were uncoupled, pushed over a hump in the tracks and silently rolled unaided before slamming into the end of a train being made up. Any new resident of Lake Como had to develop a quick tolerance for the noisy switching operations or move. The sound of the two a.m. westbound passenger train was comforting as was the rattle of incoming freights from the direction of Benbrook. Before the railroad converted to oil burners, neighborhood women used to grumble about the coal soot in the train smoke soiling clothes drying on the line. The smoke often formed a long, low black plume the entire southern length of the community, as trains worked their way up the grade and past Benbrook.

The U.S. Cavalry, Horses And Caves

In the early 1930s to about 1936 there was a National Guard Cavalry unit whose horses were stabled near the end of Montgomery Street where it intersected the Stove Foundry Road. These cavalrymen used to ride their magnificent horses through the streets, alleys, and across the many wide-open spaces between houses in Lake Como. The maneuvers usually took place in the spring and always provided a great spectacle as certain units posing as friend or enemy chased each other in and around the prairie spaces of Lake Como. There were pack mules laden with mountain howitzers and sometimes a horse-drawn caisson and artillery piece. It has been reported that in 1936 this unit was dismounted and sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to become an armored tank unit.

During the First World War this whole area was an army training base called Camp Bowie,[18] encompassing thousands of acres of land. There are stories about soldiers who were shot as deserters being buried in lost graves in Lake Como. One mysterious place allegedly connected to Camp Bowie definitely did exist and evidence of it was still visible into the mid-1930s. A cave or tunnel below ground was roughly where Bryant-Irwin Road now crosses over West Vickery Blvd which is just south of Lake Como Cemetery. The cave/tunnel originally continued directly south through railroad right-of-way evidenced by a hole opening into the vertical bank on either side of the railroad track. It was said the section on the Lake Como side was a cave containing lumber.

Meat Packing Houses And Stockyards

Swift and Armour operated two large packing plants[19] adjacent to the Northside stockyards well after the end of WWII. These two enterprises employed many African-American workers resulting in steady employment and decent wages for the times. The 1930s depression years were extremely difficult for everyone, especially black Americans. Many endured constant hunger and were ill-clothed and housed. However, those who had jobs in the railroad industry or in meat packing lived with some degree of comfort and security. This was true of the citizens of Lake Como who were fortunate enough to be employed in these particular industries. They were able to pay the rent or the loans on their homes, to buy wood fuel for the heater and kerosene for the lamps. Some even had electricity and a telephone; the more fortunate either were buying or owned an automobile. These employers[20] represented a substantial economic base and lifeline in all of the region’s communities and Como was no exception.

The Stove Foundry

The foundry was located at about Montgomery and Stove Foundry Road (Vickery Blvd), close to the TP shops. It was one of those early factories with long overhead drive shafts and wheels powering many machines connected to it by wide leather belts. The author was inside once with his father as a very young child. It too must have undoubtedly employed more Como men as laborers than the person we were there to see.

Public Schools

Lake Como’s early and perhaps its first public school was located on the corner of Bonnell and Faron Streets. Mrs. Gertrude B. Starnes was the principal, her husband the school janitor. The classes went to the sixth grade. Mrs. Theis taught first grade, second grade, Mrs. Donavan, who did not live in Como. Third grade, Miss Bryant; fourth grade, Mrs. Ruby Jones; fifth grade, Mrs. Joe Patterson, who lived in the first house on Wellesley Street and east of Arthur’s Store; and, sixth grade, Mrs. Stearns who was also the principal. For a time Mrs. Jones was seriously ill and unable to teach. Miss Carr (later Mrs. Wooten) replaced her before becoming stricken herself with typhoid fever, suffering a very long illness. All were excellent teachers, imposing strict discipline on their students, no messing around allowed. They were very dedicated women who loved their work and their students.

Students graduating from Como’s grade school in the earlier years might have gone to Gay Street School on Baptist Hill before continuing on to high school at nearby (old) I.M. Terrell. Until 1938 students used regular public transportation to go across town, because there were no school busses.

Como school had no men teachers until the school was relocated in 1936 as part of a WPA project[21] to its location up on Halloran, Goodman/Libbey. At this time, some white schools were replaced by new schools. Four older buildings from white school locations were moved all the way across town from the Northside on heavy timbers and rollers and placed on the new Como site on Halloran between Goodman and Libbey. Both of the buildings from the Bonnell/Faron site were also moved to the new site and refurbished. It was then that Como received its first men teachers. They were Mr. Thomas, Mr. Bonner and Mr. Jacque as principal. All were excellent teachers and strict disciplinarians.

San Francisco, California

2commanche7@att.net

By Charles E. Cannon

Formerly of

5726 Bonnell Street

Lake Como, Fort Worth, Texas

Acknowledgments

To my devoted wife Yvonne, and daughter Stephanie, thank you for your wise critiques and the hours of work in editing these short vignettes. You have contributed immensely to a document that expresses the deep emotional ties I have for Lake Como, the oldtimers who lived there, and to a discourse which attempts to convey a colloquial but accurate account of some events from my childhood, as much as memory will allow.

Many thanks to Dena Brown, Reuben Willburn's granddaughter, and her aunt Mrs. Frieda Willburn, wife of the late Reuben Willburn Jr. for contributing the beautiful, priceless family photographs of the Willburns at Benbrook, Texas. My thanks and appreciation also to Patrick, James and Mary Ellen Willburn, and also to Dorothy Willburn (a great Aunt of the above) for their openness to a stranger and their help in making my research a success. Patrick and James Willburn are grandsons of Church Overton Willburn.

Thanks also to James Cass, and Frank Meeks, two other surviving early Como residents. James has visited Como regularly over the years and has kept in touch with the Los Angeles contingent. His memory is superb. Frank never left Lake Como and is still there. C.C.

Visit Warm Prairie Wind's The Sunshine Special

A short account of Como's beginnings, the names of some of the first settlers and a more accurate history by Rubye Jones.

LAKE COMO, TEXAS, NEIGHBOR TO BENBROOK

1930-1945

Preface

The city of Fort Worth, Texas was established June 6, 1849[1]. Near Lake Como and Benbrook, the Clear Fork of the Trinity River makes a long curve along the southern edge of its flood plain and up against steep limestone hills and slopes, swinging north for about 2 miles and joining its confluent West Fork[2], and turning sharply east, then north, before veering south again along the city’s eastern perimeter. The resulting topography became a natural defensive position protecting the site’s western flank and it is one of the likely reasons that what is now downtown Fort Worth sits atop a limestone bluff overlooking and jutting out into the Trinity’s flood plain at the city’s northern end.

The communities to the west of Fort Worth have very interesting origins, both recent and ancient. “Recent” pertains to the mid-1800s occupation and settlement by white people[3], “ancient” relates to the geology of the region. [4] "Prior to the arrival of Anglo settlers, large herds of buffalo and members of the Wichita, Caddo, Comanche and Lipan Apache Indian tribes roamed the Benbrook area. Archeologists estimate that the area has been inhabited for some 11,000 years. Indian communities look for the same environmental factors as present communities, with the availability of an adequate water supply being a primary consideration. Undoubtedly, the confluence of the Clear Fork-Trinity River and Mary's Creek provided such a watering place to tribes as they passed through the area on hunting expeditions." (http://www.cityofbenbrook.com/content/52/85/default.aspx)

In 1930 Como lay on the very western edge of Fort Worth’s city limits which ended at Halloran Street. Beyond the next two blocks west of Halloran was rural countryside. Before the golf course was built the prairie went on, uninterrupted, except for a few scattered farms of wealthy landowners. Not much detail is available telling how Como became a semi-isolated black enclave on the fringes of west Fort Worth. Perhaps we can examine certain relevant events and deduce from them clues which will guide us to a plausible explanation.

Fort Worth Floods 1900-1908, 1922

http://www3.gendisasters.com/texas/9718/fort-worth-tx-flood-sept-1900

(THE TRINITY RIVER HAS FLOODED FORT WORTH

“…It has been many years since the waters of the Trinity have reached such a high stage. As yet no loss of life has been reported but it is reported that possibly some people have perished below this city in the Trinity river bottoms by the unprecidented (sic) overflow…”).

The excerpt above is from an early regional newspaper and it provides some clues of high potential. The Trinity River has flooded periodically for thousands of years, long before humans were here. Usually it is a placid stream, its Clear Fork flowing from the west-southwest and its West Fork flowing from the west and northwest with a high plateau watershed over a hundred square miles in size separating the two forks before they converge at downtown Fort Worth. Rainfall can sometimes be excessive, causing the river to overflow its banks and spread out over its wide flood plain, submerging everything in deep, swift-flowing waters.

The flood-prone steep slopes below the courthouse and the low-lying benchlands on the city’s eastern edge were not places where whites would choose to settle despite their closeness to town. Mrs. Corrine Clemons, who once lived below the courthouse, used to tell stories about some of these floods, how the police would knock on doors in the middle of the night telling people, "Get out, the river is rising." But it is these locations that were left which poor ex-slaves were able to claim. It took years and successive floods before the blacks living here found a racially unrestricted area on high ground that was also affordable and where a community could expand. Lake Como turned out to be that place.

Perhaps it was a combination of two unrelated calamities that made black settlement here possible; the disastrous early Fort Worth floods and the financial failure of H.B. Chamberlain’s speculative amusement park venture in West Arlington Heights.

OLD LAKE COMO

The African-American community of Lake Como not long ago celebrated its own one-hundredth birthday[5] (July 2006). The actual date of birth is an indefinite moment when the first person of African ancestry erected the wooden foundation posts for his home or moved into a structure formerly occupied by whites. This story spans only fifteen years of history, roughly from 1930 to World War II’s end in 1945. It is only a short snippet of history, albeit a crucial period in U.S. and world history, for it covers the time beginning with the disastrous financial crash of 1929, includes the rigors and trials of the Great Depression, financial recovery and victorious war in 1945. The chaos generated by both events had a great effect on Lake Como’s population as it did universally. The history of the years before and after these covered here will have to be addressed by future research and reporting.

To stand upon the ground in Lake Como is to stand upon an ancient seabed.[6] The fossilized remains are everywhere and in some places a limestone composite more than fifty feet thick. Stoop down anyplace and pick up a piece of stone, examine it, notice the swirls and ridges etched into its surface. Or go out along the old Stove Foundry Road[7] to where the driveway led up the rise to Doc Brants’ house.[8] If there is still access, stand on top of one of the vertical cuts of the roadside. Again examine the rocks at your feet; they are evidence of the region’s earliest living inhabitants, ammonites and little snails that grew here sixty-five million years ago. If it is spring, look among the stems and green leaves of the wildflowers growing out of this mix of prairie topsoil and limestone; see the live snails crawling there now, compare them with the snail fossils that look like small pebbles. These fossils’ live descendants look like they have not changed in sixty-five million years. The experience makes one feel very insignificant.

This was Comanche country and that of other tribes as well. The Chisholm Trail went through here. Lake Como, Benbrook and the whole Trinity-Brazos River watershed had to have also been Comanche territory prior to white settlement. The White Settlement Road going to the northwest out of downtown Fort Worth no doubt marks the incursion by Europeans into Indian territory. Beautiful rolling prairie, as late as the mid-nineteen-forties under cultivation or grazing land remained in many ways much as it was when the Comanche lived and hunted here.

With the spring rains came a profusion of wildflowers―Bluebonnets (Lupine), Winecups, Indian Paintbrush, Evening Primrose, Daisies, Gaillardia (Indian Blanket) and other Texas prairie wildflowers[9]― which after bloom were deprecated as weeds. Easter season was truly glorious. The earth was a natural painted canvas leg deep in the most gorgeous colors. Heavenly spring and early summer days, the sky bluer, the air sweeter and fresher, and the sunshine more comforting here than in any other place on earth. Even the storms were more spectacular in the terrible beauty of their fury.

To Remember a Fort Worth Storm

Spring and summer storms in Texas can be very violent and for those who can appreciate them also quite beautiful. Sometimes on a lovely sunny afternoon Charles’ mother or his aunt Ellen would announce, “There’s a storm coming.” Looking out from the kitchen window over the sink; a little way above the horizon in the north was a very black cloud that seemed to be advancing from the west. It moved fairly fast and its head seemed to turn south toward Charles’ house as it also filled the sky towards the eastern horizon. It was black, black, black, but the sky ahead of it and towards south Fort Worth was bathed in radiant sunlight.

As it drew closer, the clouds forming its head towered up, up, and boiled. Charles watched, fascinated and scared. He watched as its front became even with the electric power lines in the alley behind his house and as the sunlight yielded its radiance to the blackness. Suddenly the storm would strike with all of its violence. The lightning flashed and made zig-zagging streaks across the sky, sometimes flicking and trickling, lighting up the entire sky, and the thunder sounded like there were angels overhead hurling huge boulders across the heavens that collided with other cosmic stones in the distance. It sounded like explosions were right on top of the house. They echoed, and reverberated, and cascaded away into infinity and then were temporarily pacified in moments of silence, except for the roar of rain and hail which pounded the roof. The deluge plunged off the house’s eaves and down Bonnell Street’s gutters headed for Como’s swollen streams in torrents that struck obstacles and surged up more than two feet high. Often these storms were more than Charles could handle, so when the thunder sounded like it had actually hit the roof and the lightning flashes came in such quick succession that they lit up the bedroom brighter than the sun, he would duck under the bed and close his eyes and not come out unless forced out by an adult or the storm had moved on. Sometimes, when there was enough daylight left, the sky would clear and the sun would come out and shine as if there never had been a storm. Later, stars would appear in the night sky, making a million little twinkling lights and the Milky Way scattered itself across the firmament like a trail of white smoke from a prairie wildfire in heaven.

To remember Lake Como is to remember the sounds of a million frogs croaking before midnight in the streams and ponds, the melodious warbling of a mockingbird in the light of a full moon, the first distant rooster crowing at three A.M. and minutes later a nearby response, until the dawn was filled with a raucous chorus celebrating a new day; Ben Littlefield’s mules braying at sunup, the whistle of the Sunshine Special heading for El Paso in the afternoon and Momma Cannon in the backyard singing “Amazing Grace.” These sounds made Lake Como and the surrounding countryside, in early times, a truly unique and special place to live.

Except for a few small patches here and there, these expansive miles of wild beauty where buffalo once grazed, have morphed into housing developments and commercial shops.

The earliest black old-timers, who have remained here into their seventies and eighties or older, are witnesses to an epochal change like that encompassing most of the world; preparations are now underway to drill for oil and gas[10] just across from Como Cemetery. Whether they realize it or not, their personal experience of social oppression, poverty and their struggles to overcome them, their faith in God and the natural beauty of this place combined into one essence to make them who they were and are.

Lake Como Cemetery

(An Internet photograph of a wrought iron gate[11].)

Lake Como Cemetery Elegy

Most of those buried beneath that hard earth

lie in unmarked graves.

Galvanized markers long ago disintegrated.

The names and images of the dead missing

from the conversations of visitors

privileged to walk here now.

The deads' loving kin also lie at rest close by.

Or in other cemeteries far across Fort Worth,

beyond intimate mourning.

All eventually will be forgotten.

But while we who are alive still remember,

let us sing songs of mourning love.

Sing them in the verdant spring.

Sing them in summer’s scorching heat.

And cast plaintive melodies into winter’s cold winds,

November northers that blow across this bare prairie slope

when its tall grasses too have died

and brilliant summer skies turn slate grey.

Sing too, you the dead, sing your lonely notes.

Be present when we also come in death

and welcome us with laughter.

Most Unforgettable Characters

Some were pillars of the Como community, deeply religious men and women of the highest character and integrity; loving, hardworking family men who were the salt of the earth, upstanding women who worked to help support their families, who taught their children by example how to be honest, kind, helpful. These were some of the earliest settlers in Lake Como. Some were simply lovable individuals and gracious neighbors. Most of them, regardless of character or reputation, were witty, full of quick humor that separated them from the average person.

Some men were gamblers, bootleggers and self-described hustlers out to make a few opportunist dollars. A very few would be reduced to taking a life. Their common denominator was poverty and a lack of proper education. However, lack of education did not mean ignorance. Their unforgiving vocations demanded smartness, a quickness, an aggressiveness, and an intelligence comparable to that possessed by captains of industry and politics. They were “the good, the bad, the ugly,” and the beautiful.

Those men and women whose names the author has listed, out of hundreds, were chosen because of some particular memory which has significance to the writer, some told here. And because, like most early residents of Lake Como, with one or two exceptions, they have gone to their reward. So don’t look for them on the sunny side of the sod. And they are unlikely to sue the author for making uncomplimentary remarks.

Lake Como Men―

Uncle Jack Mabry

Lewis Meeks Sr.

Reverend G.W. Burton (Zion Baptist Church)

“Uncle Took”( Mr. Boyd)

Reverend Richard Weaver (AME Methodist Church

Collie Sweeney

Joe Sweeney

William Howard Wilburn, Sr. (Editor and publisher of Lake Como's Newspaper)

Will Owens

Sterling Mays

John Adkins (school custodian)

Orenthus “Baby” Meeks

Ben Littlefield

Eugene "Red" Baker

"Six" Williams

“Stack of Diamonds” Freyerson

Jeff Nelson

“Snokum” Russell

Lawrence “Brokie” Cook

John Douglas

Pop Valentine

Elijah White

Ned Slater

Robert “Kootchie” Marks (consummate caddy and golfer)

“Mummy” Marks

Garland Ross

“Pee Wee” Williams

Douglas McWilliams

“Sonny Gunny”

Lake Como Women―

Willie Cannon (“Momma Cannon,” cook for Paul Waggoner, heir of wealthy oilman W.T. Waggoner, and Helen Waggoner, whose residence was in the Texas Hotel in downtown Fort Worth)

Josie Bennett (laundry-woman, she and husband Gus raised cows and chickens)

Viola Richardson (mother of Leon Griffin)

Amelia Littlefield (strong high cheekbones, light-skinned with long dark graying hair below her waist, of black and Indian ancestry)

Sarah Mabry (cook)

Hannah Mae Mays

Eula Johnson

Mrs. Patterson (longtime Como school teacher, teacher at both schools)

Mrs. Stearns/Smith (early principal and teacher when school was on Bonnell and Faron, later married Charlie Smith when Stearns died)

Rubye (Crawford) Jones (teacher at both schools)

Miss Lois Carr (teacher at both schools)

Miss Theis (teacher at both schools)

Mary D. Lewis

Lillie Belle Patterson

Addie Latimer (white school custodian)

About Some Unforgettable Characters

Lake Como had some very colorful characters. The names of many of them appear above. Ben Littlefield, Six Williams and Red Baker were known by everyone and despite their part-time illegal bootlegging operations they were loved and well respected.

Ben was married to Amelia (Littlefield) who had a cow named Blossom, a prolific processor of Como’s prairie grasses and a producer of fine dairy foods. Blossom was a very finicky cow. Stick a finger in her drinking water and she’d refuse to touch it until the trough had been drained and refilled with fresh water.

Ben Littlefield

When Ben was not making “white lightning” with Six Williams, he worked six days a week hauling landscaping soil and whatever other work he could find for his teams of mules and assortment of mule-drawn ploughs, Fresnoes (the forerunner of the mechanical bulldozer used to move loose earth), and wagon. At day’s end he would unhitch the teams, feed and water them, bathe and dress, eat Amelia’s excellent dinner, then stick his 45 Colt revolver under his belt and mount one of the mules to go for a night of gambling. Ben was also a heavy drinker, especially in his later years after Amelia left him. He used to drink with Charlie Smith and Uncle Andy down at Smith’s Barber Shop at the corner of Faron and Bonnell Streets across from where Como‘s grade school used to be. Ben went there in a small wagon drawn by a little long-eared burro. Ben would go inside and drink himself into a stupor while the burro waited, and wait he did, sometimes all day and all night until someone would finally hoist Ben up into the wagon and say “Get up” to the burro who slowly plodded home without human guidance, down to the Stove Foundry Road across from where the golf course ends. Ben’s “live-in” woman would unhitch the critter and put Ben to bed. More than once the animal tired of waiting and went home of its own accord, leaving Ben behind.

Both Ben Littlefield and Six Williams raised greyhounds and a few bloodhounds and they hunted together down in the Trinity’s river bottom at night for raccoons, opossums and other little creatures that no one ever saw unless they were zoologists or they were Ben Littlefield or Six Williams. Some days were spent hunting jackrabbits on the prairie surrounding Fort Worth, sometimes many miles from Lake Como. Men, boys and dogs would be loaded onto the back beds of a couple of trucks and they would set off for a day of high adventure and entertainment. The animals caught would be eaten by friends and neighbors. A mixture of black and Indian ancestry, Ben is said to have lived to be a hundred years old.

Red Baker

Eugene "Red" Baker and his wife were very likely early residents. He was about six feet tall, grizzled and slightly stooped, very light skinned with a reddish hue that betrayed his mixed ancestry. He had a thick mustache, protruding reddish lips and sandy brown hair. He had a loud voice and employed it effectively to communicate his frequent anecdotes.

Red Baker lived diagonally across from Ben Littlefield on the corner of Horne and Bonnell.

His wife was dark brown and a wisp of a woman. Red and his wife to all appearances maintained a peaceful marriage, but one day something happened to break this peace. Early in the morning they began to argue, the argument got louder and angrier, soon they were physically fighting. Both were bloody by day’s end, but by sunset things were silent and people thought that all was resolved. However, not long after sunup they were at it again. Everyone expected someone to be killed but did not intervene. Again they fought all day long, stopping to rest sometimes for an hour or two before resuming the bloody fracas. The third day was a repetition of the two preceding it, but to everyone’s amazement both were still alive when it ended. No one ever knew the reason for this terrible battle. Sometime later, Red and his wife moved away from Lake Como to parts unknown and this episode in the saga of Lake Como was forgotten until now.

Six Williams

Periodically the Texas Rangers came to town and raided the stills of bootleggers, but somehow Ben, Six and Red always eluded arrest. They had friends among the local police and were usually warned ahead of time. Once the Rangers went to Six‘s place up across from where the Blue Bird Café is now to see what they could net. They went into Six’s backyard, and spotting a large tub of fermenting grain, asked Six what it was. He calmly pointed to his pen full of hogs and replied, “Hog mash.” Outwitted, the famed Texas Rangers left the scene empty-handed.

Crissy Nelson

Matriarch Crissy Nelson lived next door to the Cannon family on Bonnell Street with her three daughters and son Jeff. Over time Mrs. Nelson lost her husband, a son, a daughter and a grandson to the violence endemic to black communities, although their murders did not occur in Lake Como.

Mrs. Nelson, “Grandma Nelson,” became a mentor to young Charles Cannon because his own parents were absent most weekdays due to their employment. He regarded her home almost like his own. Mrs. Nelson counseled him as she once had counseled her own son Jeff, who had long since abandoned his mother’s guidance. A habitual dipper of Garret’s Snuff, a most foul powdered form of tobacco, she did her very best to dissuade Charles from smoking cigarettes at age twelve and was a good companion to him despite her seventy-some years of age.